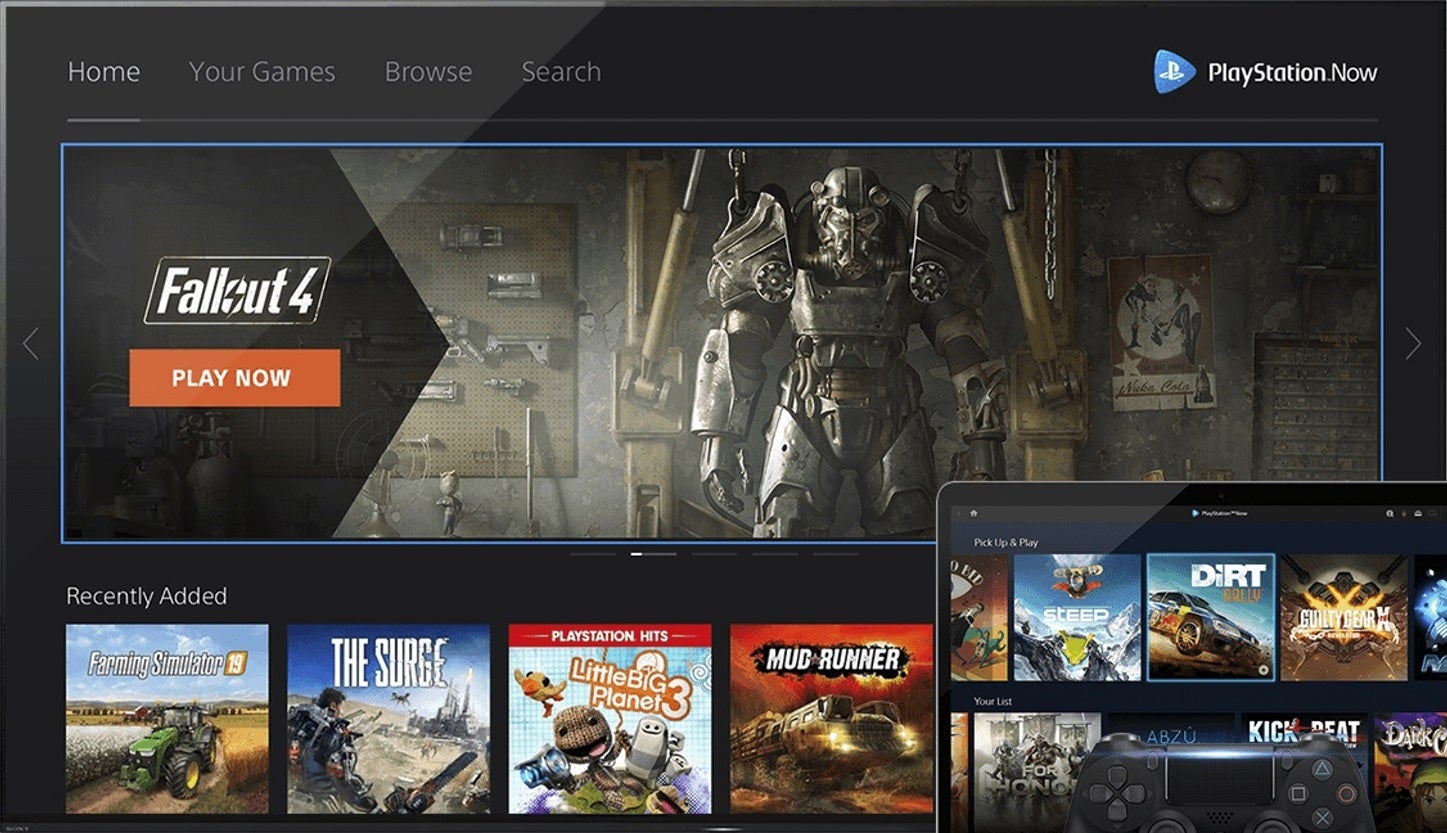

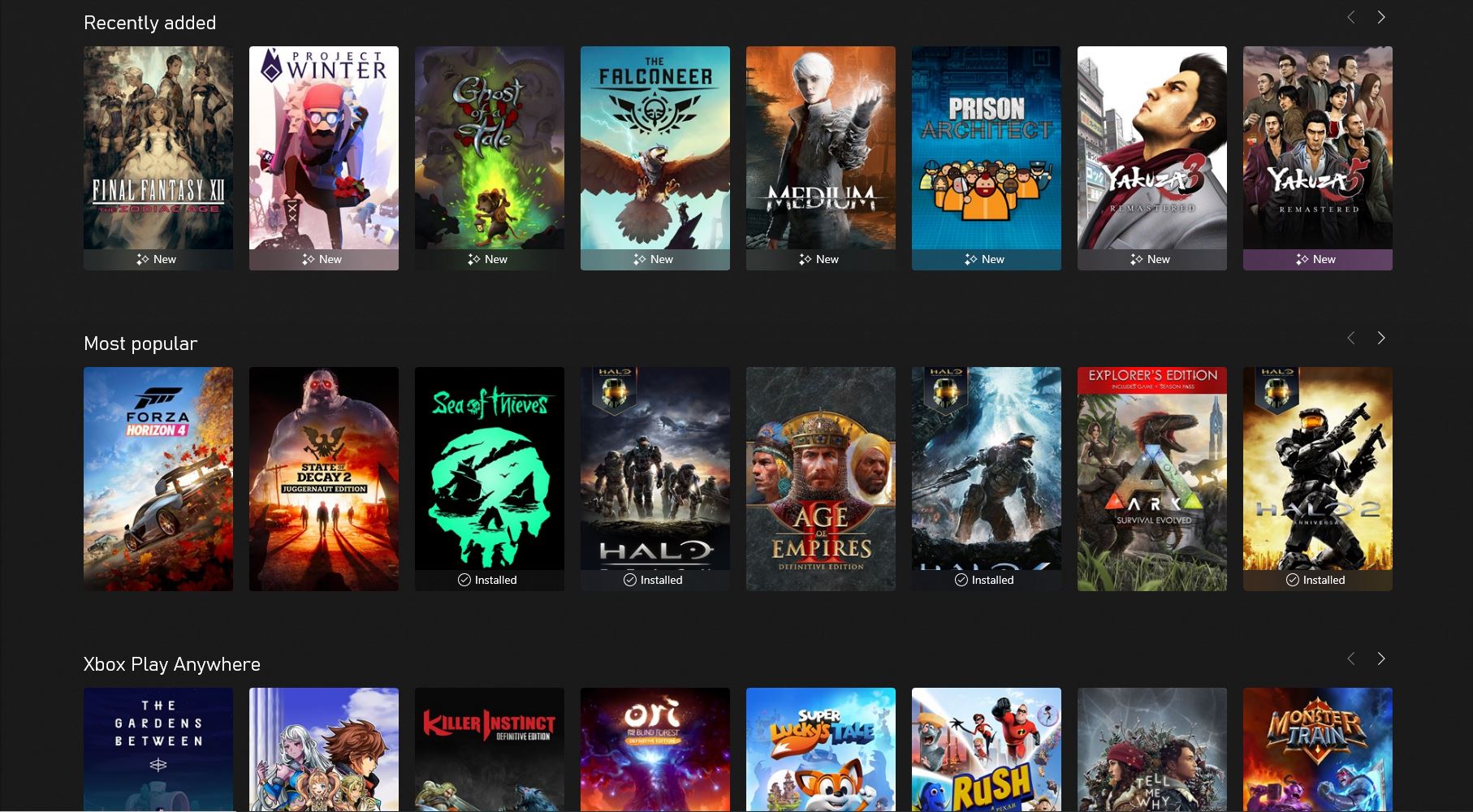

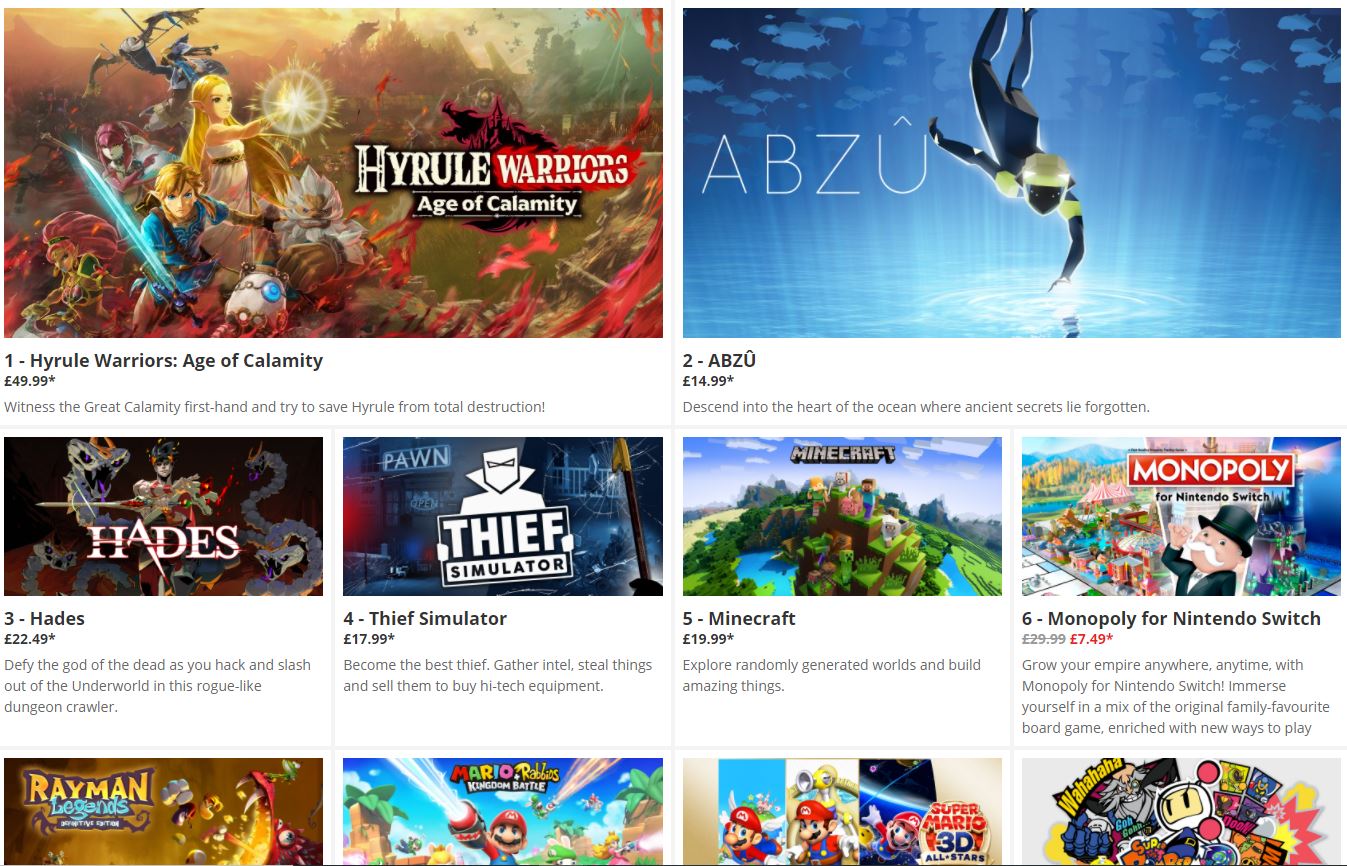

Game Pass is, officially, big. Subscribers jumped a whopping 50 per cent, from 10 million to 15 million, between April and September 2020 - before the Series X and S consoles had even launched - and have continued to grow in the months since, reaching over 18 million as of late January 2021. Putting that number into context is tricky - Xbox doesn’t do console sales figures anymore - but it’s over a third of the number of people subscribed to PS Plus, which hit 47.4 million this year, and you need that to play online in any PlayStation game that isn’t free-to-play. As for a share of audiences as a whole, Xbox Live has around 100 million active users as of this year, Steam has over 120 million, and PlayStation about 114 million. In brief: 18 million people out of a 100 million-odd, on a premium subscription? Big. The reasons for that kind of still-quite-early success (it rolled out gradually from mid-2017) are obvious: Game Pass is a steal. Right now, for £11 a month ($14 in the US), you get the online multiplayer and free monthly games of Xbox Live Gold (notably, the subject of a major price hike, then instant reversal, from Microsoft last month); plus EA Play’s 84 games and 10 per cent discount, plus the actual meat of Game Pass itself: more than 400 games, with 300-plus available on console and 200-plus playable on PC; plus a discount on permanent ownership if they leave the collection; plus day one access to every first-party Xbox game to come; plus, finally the ability to stream about 200 of them. There are caveats - a lot of those 84 EA Play games are your FIFA 15s and UFC 2s, for instance - but still. With those two subscriptions alone coming to around £70 for a year, and one brand new game at launch like, say, Halo Infinite, now reaching £60-70, some quick maths says £131.99 a year for it all is, by most accounts, a bargain. The thing is, Game Pass is such a bargain that some people are understandably worried it’s too good to be true. When new, structural changes happen fast, people get a little uneasy, and when they also happen to be weirdly good value for money, they get very uneasy. The concern is that somewhere along the magic pipeline that runs from people making games to people playing them - from developers, to publishers, to platforms, to players - there has to be a catch. Arguably the biggest of those concerns - certainly the most well-circulated - is the notion that Game Pass in its current form is just plain unsustainable, that the cost of making games, particularly the most elaborate ones, means that a measly £11 a month just isn’t going to cut it. The worry was crystallised by PlayStation CEO Jim Ryan, when talking to our colleagues at Gamesindustry.biz last September. “For us,” he said, “having a catalogue of games is not something that defines a platform. “Our pitch is ’new games, great games.’ We have had this conversation before - we are not going to go down the road of putting new-release titles into a subscription model. These games cost many millions of dollars, well over $100 million, to develop. We just don’t see that as sustainable.” The question has lingered. Microsoft actually issued that 15 million subscribers number just a few days after Ryan’s interview, displaying an uncharacteristic openness with the figures (there are some who’ve suggested the initial 10 million announcement was something of an accidental reveal), but maybe also a little defensiveness, too. We all know Game Pass is central to Microsoft’s plan for Xbox, but there’s a case for saying it’s even more important than has been claimed. It’s essential - you can expect Microsoft to be bullish in its defense. Still, the accusation has proven difficult to shake off. So, alright, how sustainable is Game Pass, really? Well, it’s potentially very sustainable indeed - but understanding why means understanding what it actually is, and what Xbox’s goal really is for it. The Game Pass we see right now, being distributed via living room consoles and gaming PCs, is actually quite different to Game Pass in its potential final form. For one, as Niko Partners analyst Daniel Ahmad tells me, Xbox is “very much in a user acquisition stage”, which is why we’re still seeing the ludicrously generous £1-for-3-months offers aiming to bring people on board. Once those people are on board, other subscriptions tell us that they’re likely to stick around. “I think the key selling point for Game Pass,” Ahmad continues, “is you have these games, you have this library, and digital ecosystems are playing a much larger role today in the stickiness of users to those ecosystems. So once people have that library, they’re very unlikely to unsubscribe, and they’re going to keep subscribing then for years to come, so they can maintain their game library and access to the games they want.” A drive for user acquisition means a drive for scale. Scale is at the heart of the Xbox plan for this generation, and arguably the foreseeable future, if they can manage it. Again, some people hear Silicon Valley phrases like ‘user acquisition’ and think of services like Uber, DoorDash or Deliveroo, similar industry-disruptors focused on changing the way things are distributed, which are still burning through venture capital cash several years after ‘scaling up’. But the difference for Game Pass is that, as the scale of Game Pass’s service increases, the costs don’t go up at anywhere near the same rate - at least in theory. For Game Pass Microsoft’s costs are predominantly up front - like, say, the “over $100 million” Jim Ryan mentioned for developing a triple-A game, or the $7.5 billion Microsoft spent on acquiring developer-publisher titan ZeniMax Media - as opposed to being incurred each time another player subscribes. Those enormous sums then also shrink a little when put next to the amount of revenue Microsoft could actually earn from its subscribers. Some very rough napkin maths: if 18m people are on the cheapest, PC or console-only $9.99 a month plan, that works out at just under $180m a month, or $2.15bn a year, if they all stuck around. The question then is less of Game Pass’s profitability full stop, but the money it can make Microsoft compared to the money it already makes now, and again that comes back to scale. Microsoft’s total gaming revenues were up 2 per cent, or $189 million, to around $9.6bn for the 2020 financial year, and Ahmad estimates that, to be profitable “to the same extent that their current games strategy is,” Microsoft would “probably want to get over 50 million subscribers out of this.” That’s a whopping number of people, but again considering PlayStation Plus is maintaining 45 million at the current time, while technically offering a lot less in return, it’s “doable”, as Ahmad puts it. “Assuming that they sell enough consoles.” Given the slightly slower start to the generation for the Series X and S than that of the PS5, that might be a bit of a concern. But again there’s a chance that misses some of the point. For Xbox this coming generation is about “going beyond the console,” as Ahmad says, “and really trying to reach as many people on mobile and PC” as possible. That certainly echoes what Xbox has to say about it. “Our goal for Xbox Game Pass really ladders up to our goal at Xbox to reach the more than 3 billion gamers worldwide,” said Ben Decker, head of gaming services marketing at Xbox, responding to Eurogamer’s questions via email. “We are building a future with this in mind.” In fact, it’s been a point echoed across the board. Sarah Bond, for instance, the corporate vice president of gaming ecosystems at Xbox - or in other words, the head of all things Game Pass - wasn’t available for interview but has spoken elsewhere about Xbox’s approach to different platforms. On the Kinda Funny Xcast Bond said: “We didn’t just talk about consoles, we talked about the whole ecosystem, everything that we were building.” What Decker and Bond are really alluding to here, of course, is xCloud, Microsoft’s ambitious, beta-stage game streaming service that comes bundled into the deal with a subscription to the £11-a-month Game Pass Ultimate. At the moment the xCloud beta is available on Android phones, but in Spring 2021 it’s due to be brought to iOS - after some initial resistance from Apple - and Windows 10 PCs. And, according to Xbox boss Phil Spencer, speaking to The Verge, it’ll be on smart TVs “within the next 12 months” from November 2020. “I don’t think anything is going to stop us from doing that.” This helps give some context to what Microsoft has been doing in parts of Asia. Xbox has partnered with SK Telecom, for instance, the largest wireless carrier in South Korea that’s also heading up the rollout of 5G in the country. You might have spotted the ads pairing Korean esports legend Lee ‘Faker’ Sang-hyeok with Tottenham Hotspur star Son Heung-Min, duking it out in a game of Forza on their Samsung phones over the cloud. SK Telecom is handling all of the marketing, meaning Xbox gets to sit and run on the back end while the service is pitched to the Korean company’s massive, ready-made user base. It’s also a rather ingenious way to quietly onboard waves of new players from a market where Xbox has typically struggled. The goal is “having that broad range of entry points into the console ecosystem as well, and then Game Pass on top of that,” Ahmad adds. “They are much more profitable on consoles, they want to keep that console user base, they want to get [players] on Game Pass, and then mobile and PC are sort of the cherry on top. And it’s a much larger cherry five, ten years from now.” Combined with the lack of major costs to scaling up the service, this is ultimately why dramatic price rises, something skeptics have long worried about, aren’t seen to be too likely (although as we’ve seen, that doesn’t stop Microsoft from trying it with other things like Xbox Live Gold). “I think Ultimate is the kind of direction that Microsoft wants to take Game Pass in, the one-price subscription for everything,” Ahmad says. He reckons there’s a good chance of more console-specific or mobile-specific price plans in the future, similar to the current PC and Xbox-specific ones available now, and those would obviously still be priced “in line with something that is going to be profitable to Microsoft,” but they would still be coming as cheaper tiers within the package, he expects. It’s the entry level tiers that might change. “We might not see a $5 [plan] anymore, but maybe another $10 one,” much the same as how we’ve seen the PC-only subscription rise from £3.99 here in the UK to £7.99 as it left beta in September 2020. In this sense, the consumer side of the ‘sustainability’ worry doesn’t seem to be a major concern. Microsoft’s goal is to bring more people in for the foreseeable future, and given there’s no explicit need to pay for dramatically rising costs, that means keeping subscriptions cheap and attractive - and competitive, as Stadia and Luna potentially find their feet a little better - for as long as possible. But there is another side to the sustainability question - one specific to the second part of Jim Ryan’s quote, on the cost of developing the biggest, most prominent tentpole games. Microsoft may do just fine, and players may be set up with a bargain for a while to come, but there is an impact on publishers to think about, too, in this subscription-based world of the future. And through publishers comes an impact on developers, and through developers, the games themselves. One of the biggest worries here comes from another industry entirely. Since its inception, Game Pass has been regularly likened to Netflix, and to a lesser extent music services like Spotify. In actuality Game Pass is obviously a little of both and a little of neither, but again the comparisons are understandable: it’s a monthly subscription, and it changes things. What really matters with both of those subscription cousins is how the biggest worries often come down to the impact on the creators. With Netflix, that idea was crystallized by a 2019 report in Deadline, which highlighted the surprising number of shows that were started by Netflix and then cancelled after either two or three seasons - a number of the Marvel-licensed series, for instance - and also how those shows are then also, allegedly, subject to exclusivity clauses, ranging from “two to three years” up to “five to seven years since the date of the series’ delivery or even longer.” (The reason those Netflix Marvel shows still haven’t popped up or been renewed on Disney+.) The fear with a potentially dominant Game Pass is not so much that we’d see an exact equivalent - most games tend not to have TV-like seasons, after all - but that the reasons for this sort of trend are also present in a gaming subscription like it, and they might have gaming-related side effects of their own. As one Wired article explained, part of Netflix’s reasoning for cancelling shows in the way it does comes down to its unique approach to using data, deciding what to make and what to renew according to not just the breadth of a given show’s audience, but how it’s consumed - if it’s finished in 28 days, say, not just if it’s finished at all. Where the similarities lie here are in the prominence of data - in Netflix using for the surgical reduction of waste, and Spotify’s algorithmic replacement of burgeoning artists. To come back to Game Pass, the real question isn’t so much the risk of sudden game cancellations, or of dodgy first-party games, but of the model itself - of whatever it is that might happen to video game production, if these data-driven subscriptions become big enough to impact what gets made and how. The thing is, with Game Pass it already has, and the talk from developers so far - at least the in-house ones, the Xbox Game Studio ones - has been very positive. Speaking to GamesIndustry.biz last year last year for instance, Tim Schafer, head of Double Fine, spoke of how Game Pass helps his studio “see where we fit in,” amidst development of the slightly out-there Psychonauts 2, and suggested that the structure might allow the team to be even more creative than before. “It does make me think about some of the crazy game ideas we’ve had,” he said, “and some of them you’re just like… I can never pitch this to any publisher. I would never get this signed. But I am now opening up that folder of documents again, and going ‘oh I really love this idea, I bet I could do that now’.” Feargus Urquhart, who heads up Obsidian, the studio behind Game Pass games like Grounded and The Outer Worlds, had similar things to say. “Game Pass emboldens us to go ‘we think this could be super cool’, and there’s people who can just try it.” While Brian Fargo, head of Wasteland 3 developer InXile, waxed lyrical about the opportunities for longer-term support for his team’s games. “We can do maybe more DLC because there are more live customers all the time,” he said, “and DLC could be something very short, very long, we can start thinking about mod communities…” Soon after Microsoft had wheeled out those big hitters to talk Game Pass, indie developer Davionne Gooden - also talking to GamesIndustry - similarly spoke of the “pretty huge” impact a Game Pass deal had on him and his game, She Dreams Elsewhere: “the Game Pass deal allowed me to fund the rest of the game, make it profitable, and still do everything I wanted to do with a publisher, without having to get a publisher.” In brief, the early signs from those developing for Game Pass have been very positive. But to really know the effects, it’s worth knowing how exactly that deal works - and what impact it has on the teams that aren’t directly owned by Xbox themselves. How Game Pass deals are structured is kept strictly private, and until recently it was Gooden who actually gave the most definitive idea of what a Game Pass deal looks like: a mixture of “upfront support,” a licensing fee, and “a bonus system of sorts, too.” Phil Spencer then elaborated on that a little more in conversation with The Verge, too: “[In] certain cases, we’ll pay for the full production cost of the game. Then they get all the retail opportunities on top of Game Pass,” he said, “… that would be a flat fee payment to a developer. Sometimes the developer’s more done with the game and it’s more just a transaction of, “Hey, we’ll put it in Game Pass if you’ll pay us this amount of money.” “Others want [agreements] more based on usage and monetization in whether it’s a store monetization that gets created through transactions, or usage. We’re open [to] experimenting with many different partners, because we don’t think we have it figured out. When we started, we had a model that was all based on usage. Most of the partners said, ‘Yeah, yeah, we understand that, but we don’t believe it, so just give us the money upfront.’” Speaking under anonymity, given the confidentiality of the deal structures themselves, this is more or less the same as what publishers have confirmed to us. With most Game Pass deals there’s usually an up-front fee for exclusivity or bringing the game to the service, which is itself definitely “enough” for a game to be worth adding, as one put it. There’s then a bonus structure broadly based on a combination of the number of times a game is downloaded, and how much time people spend playing it. How long games then stay on Game Pass themselves will depend on both parties. Xbox might want a game to stay on there after the initially agreed period, and offer the same contract again - particularly if a game’s proven popular - but the decision on whether or not to sign obviously remains with the publisher. The balance of power there is already a little different, but there’s also a bigger, more fundamental difference between Game Pass and any other subscription model that often gets missed. “When certain people try to call Game Pass the Netflix of, or the Spotify of,” Spencer says, “there is a fundamental difference… that these games are all for sale.” Xbox knows its talking points. The team has “built Game Pass as synonymous with a store,” as Sarah Bond put it, and as Ben Decker told Eurogamer the difference again is about how, “compared to other entertainment subscriptions,” players can “reengage content in new and different ways each time. This includes jumping back into a game on a different difficulty level, or exploring a game in a brand new way with add-ons or DLC. Unlike movies and TV shows, you can change the experience as you see fit to make it just as engaging, if not more, than the first time you interact - this also creates greater opportunity for post-sale monetization for developers who are interested in creating additional content for their titles over time.” The last point is the kicker here, really. The big selling point for Game Pass - for Microsoft and for developers and publishers - is that for everyone involved, the benefits go beyond the direct ones, the money up front, or earned over time, from the deal itself. It’s the network effect of what is effectively the same as a lengthy free-to-play trial for your pay-to-play game, all your friends able to play it too, on a range of platforms - and all the sales going through one store. It’s backed up by the numbers. According to Decker, Game Pass subscribers play around 40 per cent more games altogether, they play 30 per cent more genres - however you quantify a genre. Sarah Bond said developers see “engagement” go up sixfold, on average, “some go even higher than that - like 30 times up.” Most importantly though, as well as playing more, subscribers also spend more on video games themselves. Decker said “Xbox Game Pass members typically spend up to 20 per cent more on gaming than non-members”. There are specifics - Bond gave the example of No Brakes Games’ Human: Fall Flat, a relatively indie-sized game published by Curve Digital: “60 per cent of people who tried that game had never tried a puzzle game before,” she said, and “40 per cent of people [who tried it] went on and actually bought another puzzle game outside of Game Pass”. Couple that with the fact you get a discount on full ownership of a game when it leaves Game Pass, and of course how all the DLC for it, the season passes, the microtransactions, the expansions, and the rest are things you’ll be buying through Xbox’s store over their competitors, and you begin to see the bigger picture: you’re more inclined to discover, play, and spend on a game, which is good for developers and publishers, and more included to spend and play in a place where Xbox gets a cut - which is, of course, good for Xbox. Every developer or publisher we’ve spoken to has echoed that point: one told us, anonymously, that a game of theirs had “more than doubled” the money it had made from Steam in the year before it had come to Game Pass, and that the service had taken console ports of other games from something “supplementary,” or nice-to-have, to very much significant - “because of Game Pass it’s not supplementary at all.” Martin Wahlund, co-founder of Warhammer Vermintide and Vermintide 2 studio Fatshark, which is now bringing the upcoming Darktide to Game Pass and Xbox as a console exclusive, wouldn’t be drawn on sales numbers but did hint that it’s clearly worked well for the studio, telling us over email that “as you are aware, Vermintide 2 has been added to Game Pass for the second time. So the concept is something we appreciate.” Anna Downing, senior vice president of commercial publishing at Sega Europe, had similar things to say. “We’re really happy with the results and we hope [Microsoft] are too. Ultimately, they wanted quality titles, we wanted to take advantage of a great new opportunity.” As an example, Downing cites Two Point Hospital’s launch on Game Pass last year, which she says “helped propel the franchise to over 3 million players worldwide. That’s a huge benefit of being on Game Pass, it strengthens the exposure you get to a huge first-party audience… That surge in engagement in turn helps to further establish your product in the marketplace. It’s great for us and it’s great for consumers who get to experience something they may not have engaged with outside of the Game Pass model.” Mike Rose, of indie publisher No More Robots - which has brought cult hits like Hypnospace Outlaw, Descenders, and Yes, Your Grace to Game Pass, among others - is characteristically upfront about it, joking: “What more does a developer or publisher need than a shitload of players and a shitload of money?” “The last Game Pass deal we did,” he explained, “we’ve basically then just taken the money that came from that deal, and we’re now funding three more games… we’ve got four games coming out this year and three of those were essentially funded using Game Pass money.” The cyclical effect of that kind of money can be transformative for small or mid-sized publishers. “It’s taken us from ’let’s keep doing what we’re doing’ to ‘we can start funding bigger things now’ - we can really help different people out.” There are other questions for the people funding and making games, of course. When Phil Spencer, for instance, says things like “the number one metric that we see that drives success of Game Pass is hours played,” people worry that Game Pass’s reliance on continual engagement could lead to a greater emphasis on ’endless’ or service games. The fear that video games are moving away from completable, single-player games has been around for some time, of course, and generally tends to be misplaced. But if it’s that pervasive then it’s worth thinking about, at least - and these prestige, single-player games people worry about losing account for many of those that Sony’s Jim Ryan is gently alluding to, with his remark about the cost of making them. The response though, again, is broadly positive from those we spoke to. When asked about whether being on Game Pass specifically might change the way Fatshark develops it’s games - by placing greater emphasis on long-term engagement, for instance, or ‘front-loading’ the experience in some way, to stop players bouncing off the game and trying something else - Martin Wahlund was predictably ambivalent about it. “We are focusing the same way as we’ve always done; delivering the best gaming experience we possible can, no matter what platform it’s released on.” Mike Rose suggested Game Pass “definitely favours games which are multiplayer or have no ending, and can just be consistently played,” but also made the point that Game Pass relies on having new games coming to it - and therefore not just the same few endless ones - as that’s what sets it apart from competitors like PS Now or EA Play, that are predominantly older games from certain publishers’ libraries. Does Game Pass affect the types of games he signs for No More Robots? Not completely. “I wouldn’t say that it has changed how I’m signing games,” he said, but “it’s definitely on my mind.” And Anna Downing of Sega was similarly relaxed about it. “Our strategy over the last nine or 10 years has been to deliver games that are supported with content for the duration of their lifespans,” she explained, regardless of whether they’re necessarily multiplayer-focused or properly endless, like Football Manager. “If you look at the Total War games as an example, Creative Assembly has a plan for each of those games that will see free and premium content released over a period of years.” “Can that model work within a subscription service? Absolutely. Would we specifically develop games with a subscription service in mind? Potentially. It really depends on how the offerings evolve over the next few years and what consumer demand and expectation is.” One publisher put it like this: “When Steam introduced refunds, everyone was like, ‘holy shit, we need to have the best first two hours of a game ever… like everyone’s gonna play for two hours and then refund, we’re gonna lose a ton of our sales’ - but no. Maybe on average, you lose about two to seven per cent, you know, over three years or something. That’s not a substantial amount. “So concerns about creating content to match an economic model are always valid in theory. But in practice, what you find is that the way that people create games and what they want to do with games… hasn’t changed that much.” Frankly, the response from developers and publishers when asked about Game Pass, even those speaking anonymously, has been almost unanimously positive. The most popular, most oft-repeated worries seen elsewhere - about the possible devaluation of developer’s games, the impact on their freedom to make what they want, or the woes of other video or music subscriptions being felt by publishers - don’t seem to hold weight. At least not for now. Xbox is certainly confident enough. We put the sustainability question to Decker and he cited those playtime and spending figures as an example, as well as the way Game Pass has “been impactful in helping developers find new audiences which leads to increased adoption, a diverse catalog of titles and increased playership for various games.” The point he was making was pretty clear. In his words: “Xbox Game Pass is sustainable.” There was one other sticking point, though. Not about the impact on how games are made, or funded, or the model’s sustainability itself - but about how it can change the way they’re distributed. One of the great points of contention in the publishing world is the practise of curation - or the lack of it. On the one hand, in allowing almost anyone to publish a game directly to a platform with a huge audience, for little cost, the flatter, more democratic storefronts like Steam where almost anything gets published are often seen as having played a revolutionary role in the rise of indie games - and just the sheer number of good, surprising, or unusual break-out hits in general. On the other, smaller games can just as easily get drowned out amid the huge numbers that arrive on the store each day as they can break out to success - and the laissez-faire approach of platforms like it can lead to something of a wild west, too. Steam’s certainly had its fair share of troubles. As far as Game Pass is concerned - and indeed other subscriptions, like Apple Arcade - curation is very much the goal. “A lot of people look at [Game Pass] and think about it as a value play,” Sarah Bond said, “but what we’ve learned, and what came out in the research we did when we designed Game Pass, is people want value, but they really wanted curation. [And] that oftentimes it’s super hard to find something out of 2000 titles - like, where do I go? - and [players] wanted this ability to have this trusted place where you’re like: ‘I know, I’m gonna look at Game Pass, I know someone looked at that portfolio in detail, these games have been really vetted, this is something that’s gonna be really great’. And that is a ton of the value that we see right now.” Decker said the same thing to us directly. The move towards curation “is intentional,” he said. “Members asked us to prioritize title quality over quantity, and to ensure the library is updated regularly so there’s always something new to play. We curate the library with the diversity of our 18 million members in mind, taking into consideration factors like genres, age ratings, broad or niche appeal, and more. It’s not intended to be filled with thousands of games - and our members have said that’s their preference - additionally, a curated library helps developers with discoverability.” But some publishers would argue the opposite. Michael Douse, director of publishing at Larian, the studio behind the Divinity: Original Sin games and Baldur’s Gate 3, emphasised that Game Pass is “fantastic” in a range of ways, with benefits that “can’t be understated” for a lot of game-makers, and was generally at pains to stress that this is all very much just a hypothetical, worst-case possibility, but made the point on curation to us like this: “Gaming has been crawling away from the retail shelf for years. Games used to be made for shelves. The retailer would say, ‘Well, we need an action game here, we need an RPG here,’ and then there would be a deal to be on [a certain] space on the shelf, et cetera.” “In a sense, in a traditional ‘publisher sense’, [games] weren’t created for players, they were created for retail spaces. Digital distribution broke us out of that, we got away from that.” He cites the various tools on platforms like Steam - wishlists, top sellers sections, latest releases lists and the like - as ways in which games can be surfaced to the right people without having to use curation. “If you sell enough copies, you can do a visibility round. If you’re a new game, you get the carousel, the top sellers - these are all great things, because it puts everyone on even terms.” “Now,” he continues, “algorithmically, if I’m making something, the people who might like that something will magically see that something - which is obviously a better way, because now you’re making games for humans, you’re not making games for retail space. My concern, I suppose, is that maybe we risk going back to that state where actually you’re making games for catalogue strategies - i.e. retail shelves - and less for players.” Console stores themselves have just begun to catch up, he adds, pointing to the Nintendo Switch’s store as one of the first to properly mirror Steam, with the PS5 and Series X consoles now doing the same. “That’s why indies have been so successful on the Switch: you can have editorial content, you can wishlist, and it’s democratic. If you’re a new game on Switch it doesn’t matter what you are, you’re right next to, I don’t know, the latest Wolfenstein or whatever - because you just happen to be releasing around the same time.” In this sense, moving to a subscription model can leave you in a bit of a bind, especially when accounting for the data-reliant side of subscriptions - like the data-driven strategies of Netflix and Spotify outlined earlier. “When you’re data-driven, data is brutal… there’s no empathy in data.” “I have no idea [about] the way that these things are curated, but what I would say is that I would certainly trust, you know, the players. My point, explicitly, is that I would always rather have our fate in the hands of the players than anyone else.” “Always, always the players. I would want to talk to the players, I want to talk directly to the players, I want them to decide, or to have a dialogue with them, they should be the ones who decide whether or not a game succeeds or fails, I think.” Still, the point remains a hypothetical, and specifically one that relies on Game Pass not just becoming popular or hitting the targets of so-many-million subscribers, but subscriptions as a whole becoming the dominant force in how people get their games. For now, that’s a very long way off - and every publisher that we spoke to had the same point to make about it: that Game Pass is just one “part of the mix,” as Wahlund said. Another “important opportunity” to bring Sega’s games to as many people as possible, as Downing put it. Or that “Game Pass is just one entry point” into Microsoft’s own ecosystem itself, as Ahmad explained, too. In a way it comes back to Xbox’s very publicly stated goal: a “low barrier to entry,” as Ben Decker said, so “at the end of the day, [people] can simply play more games however they prefer to play.” Maybe the most soothing response to the fears of a subscription future came from Michael Douse himself. “I like to say that Nintendo is a good example of this, because Mario in the 1980s, and Mario now, hasn’t really substantially changed.” “People just want to sit in front of a TV and goof around on a controller in levels. And that will never change. Gaming is so ridiculously stable that even if there are viable economic concerns, people will want a specific thing, and people will want to make a specific thing - and as long as those two things align, it doesn’t really matter what the economic model will be behind them.” “How many fucking Adam Sandler movies are there on Netflix - and why?! But on the other hand, Uncut Gems is striking. These things even themselves out, right? So it’s not all doom and gloom - there are clearly way more positives to subscriptions, in the short term and the long term.”